Chapter Three

THE SWIMMING HOLES

The Good and The Bad, Bloodsuckers, Ice

Many of the books for boys that we signed out at the Town Hall library had stories about swimming holes. Tom Sawyer had one plus the whole Mississippi River. We boys had two: the New Haven River and Allen's Pond; but getting to either was never easy because they weren't close and summer was our busiest time on the farm.

After a day in the hayfield, guiding the horses, riding the mower, fighting the dumprake, tedding the hay to dry it, or pitching it up by fork onto a hayrack -- hoping your brother would get it properly loaded so it wouldn't fall off half way to the barn -- unloading it in a hot and suffocating mow with an accumulation of scratchy hayseed inside your shirt and bib overalls and sweat running down out of your hair and into your squinting eyes, then your primary thoughts were of a single thing: plunging headfirst into a wonderfully cool and rejuvenating river or pond.

Our favorite was the New Haven River, ideal in every respect except for the distance and only feasible on Sunday afternoons or when Dad would excuse us from evening chores.

It was nearly a mile down to the Gill boys' farm and we three, Edward, Richard and Paul, accompanied by our "mostly Shepherd" dog, Rover joined the three Gill boys there and together we walked -- and sometimes ran -- a half mile further to the river.

Our chosen spot was not far from the road and was partially screened by a grove of trees and a cornfield so that the swimsuits we carried were seldom worn.

It was ideally situated. The shape of our swimming hole was as if designed. A large granite remnant of the Ice Age had turned and slowed the river at that point, redirecting its flow and creating and continuously freshening a deeply shaded and relatively quiet pool, while the main stream hurried around the shoulder of the rock and turned, racing into the narrowing downstream channel.

Opposite the rock face, across the river, was a little beach where the rising waters of springtime had deposited sand and loam from the river bottom as it slowed around the rock barrier. Scattered branches and broken limbs lay at its edges.

We threw off our bib overalls and tennis shoes and leaped, yelling, into the pool. Rover hesitated, ran tentatively along the bank and finally barreled on in.

We cavorted, held our breaths and swam to the bottom, pursuing and trying to snatch the elusive young trout that darted among us. We competed in trying to see who could hold his breath the longest. Climbing to the highest point on the rock face, we jumped and dived to the point of near exhaustion.

Finally, worn out with the competition, we emerged, scampered across the sun-baked rocks, plunged into the short channel and swam across to lie on the sand, rolling to avoid one very wet dog determined to stand among us as he shook the water from his streaming coat.

It would be well after dark when we reached home and Mom would scold us, "How was I to know one of you hadn't drowned? Don't ever do that to me again," while she served "my three boys" a belated supper.

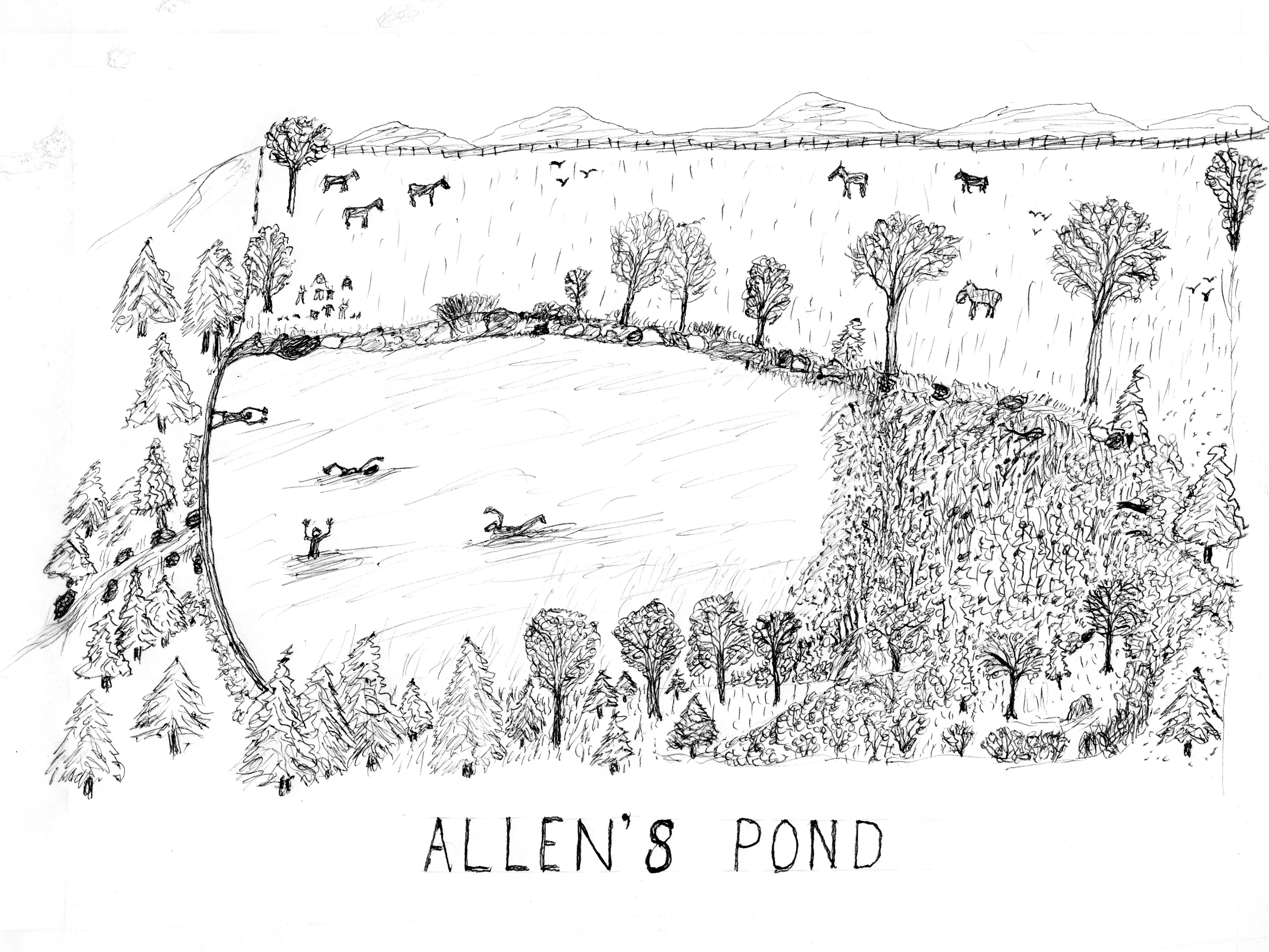

Our alternate swimming hole was Allen's Pond. It was situated between Brown's Hill and Cemetery Road, fed by a valley stream. It had been dammed up for farm purposes and in winter it provided a source of ice for cooling milk.

A good feature was that it placed us much closer to our favorite cousin, Paul Conroy, who lived at the foot of Town Hill, and we could often arrange to meet him there.

The pond had some negative aspects, however. Its source seemed to be the swamp located farther up the valley and the cows not only drank from it but slogged around in it up to their udders and occasionally relieved themselves in the shallows so that the color of the pond was not particularly inviting for swimming. There was always an opaque reddish-brown hue and brackish tinge to the water.

At the higher end of the pond a myriad of weeds, water-lilies and bulrushes were slowly encroaching on the open areas. Though the pond would not be inviting to a discriminating adult, it was cool and wet and acceptable to hot, tired and sweaty boys.

There was one feature of the pond we did not reveal to newcomers: it was a haven for bloodsuckers (leeches). These fat little worm-like creatures, not much more than an inch and a fraction long, would attach themselves to your body, desensitize a spot near a blood source and ingest significant quantities of your blood. Since we habitually swam naked, it often required intensive scrutiny by others to locate them all. They couldn't always be detached by a simple pull of the fingers so when we swam at the pond we would bring along a pair of pliers. Sometimes a bloodsucker would find a lucrative source between someone's toes and remain undetected until apprehension dawned on the way home with a squishy feeling in one's shoe.

Our use of the pond for swimming was limited to a couple of years, just long enough to provide entertainment from unsuspecting newcomers who discovered our secret -- to their horror.

In winter, that secluded little valley's nights were long and frigid and the ice froze to nearly eighteen inches thick. It was there that the dairy farmers would come with horse-drawn sleighs and cut blocks of ice for storage in their "ice houses," insulated with sawdust around and between the individual blocks, for use in warm months to cool the milk overnight before the morning's trip to the creamery.

The pond was a convenient place for ice skating. Sometimes we would come at night and build a fire from scraps of wood and have skating parties. Our skates when young were a type that came with a key and straps. Clamps, both front and back, would fasten to the sides of our shoes and were tightened with the key. The straps would reinforce the whole and we would step out, hopefully more on the blades than our ankles.

It would not be until several years later and more prosperous times that we would come into possession of real "store bought" hockey skates.

In later years I was reminded of the pond when I listened to an irate classmate vilify his landlord with, "He's a friggin' bloodsucker," and I thought, "Take it easy. He only wants money."